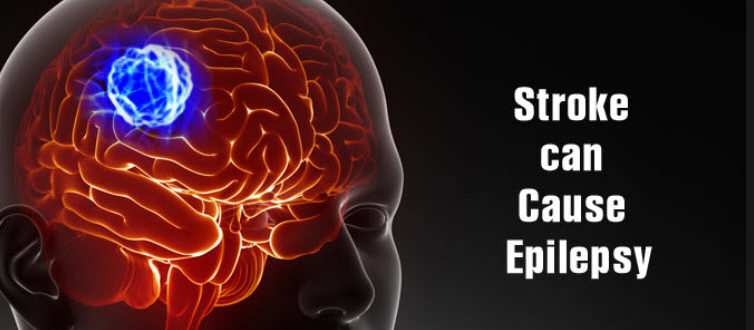

Stroke is one of many conditions that can lead to seizures, or epilepsy. You may think of these as ‘having fits’. In the UK this condition affects just under 1% of the population. Around 5% of people who have a stroke will have a seizure within the following few weeks. These are known as acute or onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke.

Stroke is one of many conditions that can lead to seizures, or epilepsy. You may think of these as ‘having fits’. In the UK this condition affects just under 1% of the population. Around 5% of people who have a stroke will have a seizure within the following few weeks. These are known as acute or onset seizures and normally happen within 24 hours of the stroke.

The good news is that your risk of having a seizure lessens with time following your stroke. But, you’ve really got to take care. I see people regularly who have fits for the first time. It’s never fun, but luckily, as someone who has had controlled epilepsy for over 20 years I know exactly how to identify these very early (it’s not that hard really). Quickly get the person to the floor, gently, into the recovery position and call for an ambulance. If you have a list of all their medications on hand to tell the paramedic, that would be ideal.

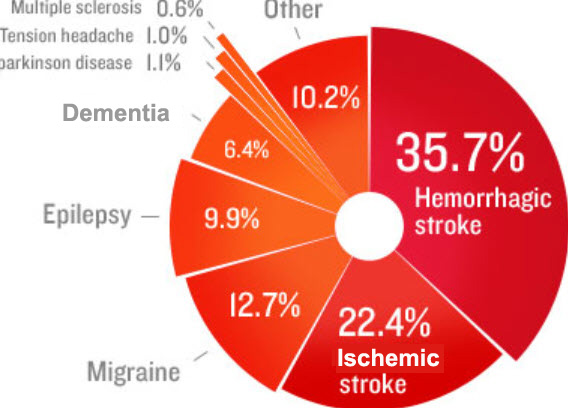

You are more likely to have had one if you have had a severe stroke, a haemorrhagic stroke or a stroke involving the part of the brain called the cerebral cortex. My own epilepsy came only after subarachnoid haemorrhage, (an uncommon, very serious and often fatal type of stroke caused by bleeding on the surface of the brain)

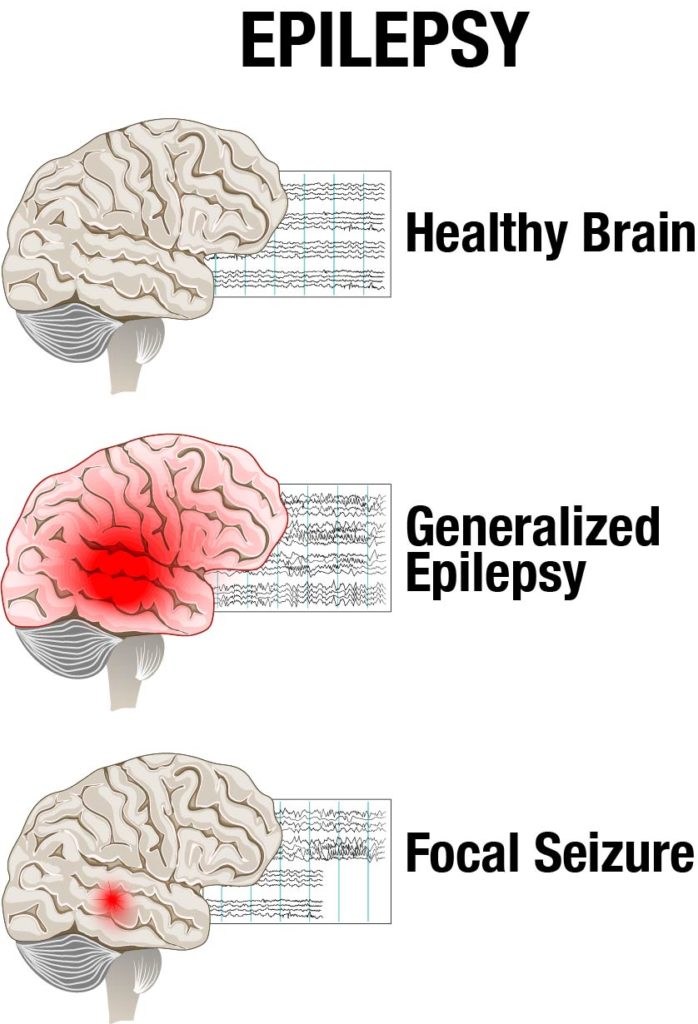

The causes of seizures are complex. Cells in the brain communicate with one another and with our muscles by passing electrical signals along nerve fibres. If you have epilepsy this electrical activity can become disordered and a sudden abnormal burst of electrical activity in the brain can lead to a seizure.

There are over 40 different types of seizures that can occur, but the most common ones are partial seizures or generalised seizures.

Partial or focal seizures only occurs in part of your brain. You may remain conscious and aware of your surroundings during a partial seizure (called a simple partial seizure) or you may become confused and unable to respond (a complex partial seizure). The symptoms you experience during a partial seizure will depend on which part of your brain has been affected. You may feel changes in sensation such as a tingling feeling, which spreads to other parts of your body.

Commonly people experience a rising feeling in their stomach (a bit like when you go over a humpback bridge). This is called an ‘epigastric rising sensation’. You may also experience uncontrollable stiffness, twitching or turning sensation in a part of the body such as your arm or hand, and/or disturbances in your vision, such as seeing flashing lights.

People can actually be taught to ‘ward off fits’! I learned the hard way how to do this. It’s a real trick of the trade you can use as a stroke survivor! Jut get in touch with me and I’ll tell you how I do it. 2004 was the last time I personally had a fit. I developed a 3-stage process which is remarkably successful. Part psychological and part-physical, it just works for me and might work for you too.

People can actually be taught to ‘ward off fits’! I learned the hard way how to do this. It’s a real trick of the trade you can use as a stroke survivor! Jut get in touch with me and I’ll tell you how I do it. 2004 was the last time I personally had a fit. I developed a 3-stage process which is remarkably successful. Part psychological and part-physical, it just works for me and might work for you too.

Since 2004 and 2019, I’ve controlled my fits and manipulated the levels of the drug in my body so that it can cope with changing body-weight. Putting on muscle was the main reason why I had to increase the dosage of my pills. More on anti-convulsants (or anti-epileptic drugs) below.

Generalised seizures involve both sides of your brain. There are several types of generalised seizures. Tonic-clonic seizures are the most common and widely recognised type. During a tonic-clonic seizure you lose consciousness, your muscles go stiff and you usually fall backwards. I used to fall forwards. I know this because I used to wake up not knowing what had happened to me, but seeing a massive carpet-burn on my forehead. You really do basically stiffen up and go down like a brick!

After losing consciousness, your muscles tighten and relax in turn, causing your body to jerk (convulse). Your breathing may become difficult and you may lose control of your bladder. This convulsive phase of the seizure should only last a minute or two.

Other types of seizures include tonic seizures (where your muscles go suddenly still but you do not have convulsions), clonic seizures (you have convulsions but no muscle stillness beforehand), atonic seizures (you suddenly lose all muscle tone and go limp), or myoclonic seizures where you experience a brief muscle jerk similar to the jerk you sometimes get as you fall asleep. A secondary generalised seizure is when a partial seizure spreads to both sides of the brain. Stroke-onset seizures are often of this type.

Most seizures stop by themselves and last between two and five minutes. After a seizure you may feel tired or confused. The time it takes to recover varies from person to person. Sometimes after a seizure associated with stroke, you will have temporary weakness, which may last for a few hours.

If a seizure lasts for 30 minutes or longer, or you have a series of seizures without consciousness being regained in-between (status epilepticus), your body struggles to circulate oxygen properly and this is an emergency. Your family or carer should call emergency services immediately if you have a seizure that lasts for more than five minutes or if one seizure follows another without you regaining consciousness in-between.

IMPORTANT: If you think you have had a seizure, and are not in the hospital, you should see your GP immediately, and then referred as soon as possible to a specialist. You may not be able to remember the seizure so if someone else witnessed it, it might help if they see the specialist with you. The specialist will ask you questions about what happened. This may be enough to make a diagnosis. However, further tests may be needed, particularly if the seizure did not involve convulsions.

You may have an electroencephalogram (EEG), which involves placing electrodes on your scalp and is painless. These measure electrical activity in your brain and can identify any unusual patterns. An EEG only shows what is happening in your brain at the time it is done, so a normal EEG does not necessarily mean that you do not have epilepsy.

It’s a good idea to keep a ‘seizure diary’ with the dates and times of your attacks, what happened, and any possible triggers, such as alcohol, or stress. It means you can narrow it down to factors such as: ‘am I missing taking my pills by half an hour to an hour?’, or ‘have I just been in very stressful situation?’ Both of these were big triggers for me. Flashing lights can be a trigger (photosensitive epilepsy) though this is not common as people think.

There is currently no cure for epilepsy, but medication can usually control seizures and allow you to lead a normal life. Which treatment you have will depend on the type of seizures you’ve had, how frequent they are, other effects of your stroke, for instance if you have problems swallowing, and any other medication you are taking.

Anti-epileptic medications (AEDs) work by preventing excessive build-up of electrical activity in the brain, which is causing the seizures. Unfortunately, the normal activity of the brain can be affected, leading to drowsiness, dizziness, and confusion amongst other side effects. Once your body is used to the medication, these side effects may disappear.

Anti-epileptic medications (AEDs) work by preventing excessive build-up of electrical activity in the brain, which is causing the seizures. Unfortunately, the normal activity of the brain can be affected, leading to drowsiness, dizziness, and confusion amongst other side effects. Once your body is used to the medication, these side effects may disappear.

Your doctor may start you on a low dose and increase it gradually to reduce the chances of unpleasant side effects. If you can’t tolerate the medications, then you must tell your GP as there are choices of treatments, and the science is progressing all the time. There are many safe and reliable AEDs available, and you will find one that suits your individual case. The choice of AED used for you will depend upon your type of epilepsy, sex, and any other medications you may be taking. I take the above medication: the good thing about these is you can get the Chrono-Release version, which release the medication throughout the 12 hour intervals per day you should take them.

Many people, including myself, get back to extremely busy schedules after stroke, and simply take their pills. One tip is that often AED dosages are often quite highly-tuned. If you put on bodyweight, you may begin to have enough in your system without realising. This was a total ‘game-changer’ for me and has been so for many others. It’s also a good idea, if you are having fits, to get a medical bracelet which identifies you as someone who experiences epileptic fits..

Important tips:

- Develop your own ‘early-warning system’ and find out how to ward off fits as they come on.

- Find an excellent Epilepsy Consultant: they are worth their weight in gold.

- Never suddenly stop taking your medication: this will cause you to have seizures and possibly develop prolonged seizures (status epilepticus). Although studies show that the risk of having a seizure-related accident decreases as the length of time since the last seizure increases, there are still a great deal of road traffic accidents found to have been caused by people coming off anti-convulsants. Medication should only be stopped with medical supervision.

2 Comments

Hi Tom,

Hope you are well,

I had major seizure 2 years after stroke. Fortunately Kev had First Aid and put me into recovery b4 calling 999, so I survived. Epilim discontinued few years back after fits eased off although consultant thought there was always possibility. I think we should have been warned not left to find out!

Bryony

Been taking 1.4 grms of Epilim daily for 20 years , following severe Haemorrhagic stroke..

Have now developed severe tremor. Suspect, as side effect of Epilim