Recent large-scale, longitudinal studies have reinforced the established understanding that hypertension is a critical antecedent to cerebrovascular events, including stroke. Contrary to the misconception that strokes can occur unpredictably in otherwise healthy individuals, observational data from vast populations indicate that almost all individuals who experience a stroke exhibit underlying cardiovascular risk factors, most notably elevated blood pressure, for years preceding the event. This extensive body of research, including cohorts followed for up to two decades, underscores the importance of long-term preventative strategies over reactive responses to acute crises.

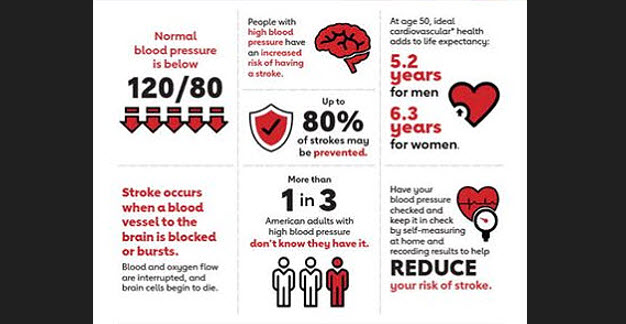

The mechanisms linking chronic hypertension to stroke pathogenesis are well-documented. Persistent high blood pressure exerts mechanical stress on the arterial walls throughout the body, including those supplying the brain. Over time, this contributes to the stiffening and narrowing of arteries, a process known as atherosclerosis. These changes facilitate the build-up of fatty plaques, which can rupture and cause clots, leading to an ischemic stroke. In smaller vessels, chronic hypertension can lead to microvascular damage, increasing the risk of haemorrhagic stroke. The cumulative effect of these pathological processes highlights that stroke is often the culmination of a long-term, progressive vascular disease rather than an isolated, sudden episode.

This profound insight has significant implications for both clinical practice and public health policy. Traditional clinical approaches have often focused on short-term management and the immediate post-event phase. However, the data now clearly argue for a more sustained, proactive approach to hypertension management across the lifespan. Population-level screening and health monitoring programs are vital for identifying individuals with non-optimal blood pressure years before a potential stroke.

By leveraging routine health data, healthcare providers can intervene earlier with lifestyle modifications and pharmacological therapies to manage blood pressure effectively. Evidence from landmark clinical trials, such as the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), has demonstrated that intensive blood pressure control (targeting a systolic blood pressure below 120 mmHg) can significantly reduce the risk of stroke and other major cardiovascular events in high-risk populations.

The message is clear: stroke prevention is a marathon, not a sprint. The groundwork for a stroke is often laid years in advance, with hypertension as a persistent and identifiable warning sign. Shifting the focus toward long-term risk factor management, guided by routine monitoring and evidence-based interventions, offers a powerful strategy to reduce the incidence and burden of stroke in the UK.

This requires a concerted effort from clinicians, public health officials, and individuals to recognise and address the silent threat of hypertension long before it manifests as a debilitating cerebrovascular event.