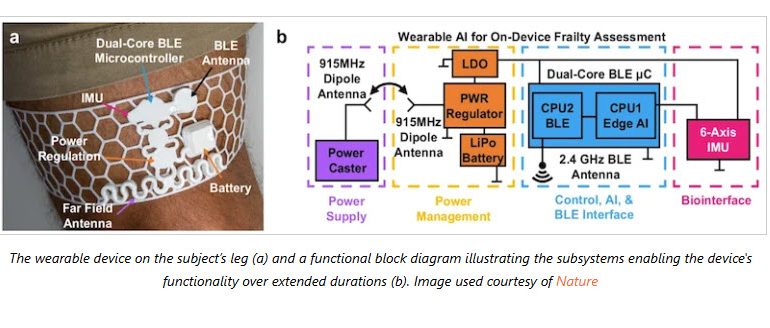

The mechanical implementation of the 5.5-pound hip exoskeleton represents a quite innovative shift in wearable robotics, as it addresses the metabolic inefficiencies associated with hemiparetic gait. Developed at the University of Utah within the HGN Lab for Bionic Engineering, this research was spearheaded by principal investigator Associate Professor Tommaso Lenzi and lead author Kai Pruyn. The clinical findings, published in the journal Nature Medicine in October 2024, establish a new precedent for portable assistive technology. While previous attempts at stroke-specific robotics focused heavily on correcting foot drop via ankle-based systems, these often failed to reduce the physiological effort of walking because patients frequently compensate for distal weakness by over-recruiting proximal hip musculature. By targeting the hip joints directly, this device places the mechanical workload closer to the user’s centre of mass, allowing for lower torque requirements and a significantly lighter battery-powered motors system compared to cumbersome ankle-driven alternatives.

The trial utilised rigorous motion-capture techniques and instrumented treadmills to analyse the biomechanics of seven participants with hemiparesis. Data indicated that the intelligent control system, which synchronises with the user’s gait to provide a boost during hip flexion and extension, offloaded approximately 30 per cent of the biological work from the hip joints. This mechanical assistance resulted in an 18 per cent reduction in the metabolic cost of walking, a figure that provides a substantial relief equivalent to a healthy individual removing a 30-pound backpack. Such an improvement is critical because post-stroke fatigue often stems from the excessive caloric expenditure required to initiate and maintain a paretic step. Furthermore, the real-time customisation of assistance levels on each side allows for a symmetrical gait pattern, which is a primary goal in neurorehabilitation.

Beyond the immediate energy savings, the qualitative results from study participants like stroke survivor Lidia suggest that the device may facilitate secondary neuroplastic benefits. Her observations indicated that consistent use of the exoskeleton appeared to improve her unassisted movement, suggesting that the ‘boost’ provided by the robotic thighs helps the brain re-learn the correct timing of muscular engagement. This synergy between wearable engineering and biological recovery represents a sophisticated advancement in the treatment of one of healthcare’s biggest unmet challenges. The success of this hip-centric approach, following the lab’s previous acclaim for the Utah Bionic Leg, reinforces the potential for wearable robotics to transition from laboratory experiments to functional tools for daily living.

Although this technology has demonstrated life-changing potential in a laboratory environment, it’s not yet available for stroke survivors in the UK to buy. The research team at the University of Utah is currently partnering with leaders in the prosthetics and orthotics industry to transform the prototype into a commercial product, a process that involves extensive safety testing for home environments and the acquisition of necessary medical regulatory approvals.