The majority of stroke survivors whom I’ve met, when describing their prior physiotherapy and any other rehabilitative efforts, will report that the focus of therapy was usually on seated stabilisation, seat to stand, weightbearing and walking practice. All vital stuff. But only a small minority remembered being introduced to/practising upper limb exercises.

This happens for a number of reasons, but as time and resources are most usually limited, therapists often do not have time to devote to extensive hand-function efforts. Many receive no upper limb therapy at all. And by the time further treatment is sought, the task is all the more harder. At the height of the pandemic, many patients were told that it was safer to go home and receive no therapy or no further therapy.

This is why it’s critical that the leading edge Upper Limb Clinic developed at the Institute of Neurology at UCL by Professor Nick Ward builds up more and more a body of evidence of efficacy so that it becomes clear that a ‘3 week intensive blast’ of multi-therapies that such a Clinic can offer, with the learning for survivors and families that can accompany it, can become an effective bolt-on or plug-in funded for each hospital in the UK with a stroke unit in order to push/promote/kick-start recoveries. Maybe this will happen in due course. I hope so!sive

In the meantime, it’s vital that stroke survivors are shown what to do as far as upper limb is concerned in the community, as soon as possible after discharge, in order to continue the work of the therapists or initiate it if none has yet been done.

The reason is that all evidence points to the fact that high dosages of repetitions, over time, stand best chance of assisting upper limb recovery. This has to be done by the survivor, at their own residence. Survivors need to know what to try to do themselves and what they need to seek help with/for.

The evidence (see yearly-updated in-depth reviews of well over 4,500 studies including over 2,170 randomized controlled trials at www.ebrsr.com) reveals that:

- Task-specific training, alone or in combination with other therapy approaches, may be beneficial for upper limb function.

- Higher and lower intensity task-specific training may have similar effects on upper limb function.

- Trunk restraint with reaching training may improve upper limb function.

Let’s discuss how you as a stroke survivor can use this evidence. Remember, high dosages of repetitions (of reach, grasp and release) are needed. Remember that all attempts at repetitions (including mental practice) drive neuroplasticity. You NEED to get it done, over and over again, even if nothing is happening: there are ‘tricks of the trade’ as it were’ that you can use.

I’m going to show you all of this in a series of Youtube clips.

You can go ahead and get access to the full series of videos on physical DVD or anytime online streaming access, if you like, by going clicking to here The Successful Stroke Survivor Full Video Series 300 minutes.

Have a look at this small video I put together: this is clip 1 of 20 or so about upper limb training. Then take part with me by subscribing to the new ARNI Stroke Rehab Tips on Youtube. Upper limb rehab will come first and Video 1 is already up on there: watch and subscribe for further Youtube videos! Many other stroke rehab topics will be loaded up on there as time moves on.

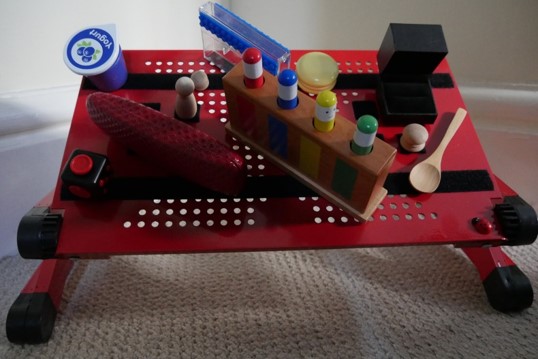

If you do want to take part, you need only a minimum amount of kit. A short stick (cut a broomstick and chamfer the edges), a tray or book, some items with blue tack stuck to the bottom (or MUCH better a laptop board with heavy duty Velcro strips attached and some specific items with Velcro squares attached to them – click the link to get, or make your own board).

Being in a seated position is fine when doing upper limb task-specific training. But completing the reaching task by moving your trunk forward to complete a reaching activity is ‘cheating’. This is where trunk constraint works well. This is often done via a chest seatbelt/harness.

Being in a seated position is fine when doing upper limb task-specific training. But completing the reaching task by moving your trunk forward to complete a reaching activity is ‘cheating’. This is where trunk constraint works well. This is often done via a chest seatbelt/harness.

How to start retraining your upper limb after stroke? Your starter programme consists both of stretches and tasks. You may or may not have been taught how to safely self-stretch but the idea is that more is better and safety is paramount. You have to stretch your upper limb (gently), knowing at the same time simply stretching won’t bring recovery. You have to be task-focused. So, when you do a stretch, you then do something challenging and specific functionally with the stretch.

For example, stretch, then try to pick a hairbrush up and put it into a cupboard. In your retraining sessions, stretches must be considered as promoting the chances of the successful performance of the task.

Remember my upper limb catch-phrase: stretching enables the task and extends ‘time on task’.

Remember my upper limb catch-phrase: stretching enables the task and extends ‘time on task’.

These are very important for improving your potential ability to reach for, grasp and release items with your hand: activities that are denied to so many stroke survivors. You can use stretches daily in order keep muscles long and prevent further complications. The best results are often seen in people who have consistently stretched their wrist, fingers and thumb on their more-affected side from a very early period in the hospital.

Upper limb task-specific practice concerns reaching (which you perform mainly with your shoulder, elbow and wrist joints) and grasping/releasing (which you do mainly with your fingers and thumb joints). Stroke survivors often find it very hard to make purposeful movements requiring precise control of either; rendering movement slow, inaccurate, and usually not well directed or coordinated. Isolated recovery efforts for the upper limb, often in terms of grasping and releasing an item during a task, correspondingly demand effort and accuracy.

Unlike (to an extent), lower body, training coping strategies for and during rehabilitation of the upper limb should be largely avoided.

If you have spasticity and find it hard to reach away from your torso, you may tend to ‘throw’ your more-affected arm at a task mainly by activating your shoulder joint. This stands in contrast to a more controlled movement sequence, where your arm can move away from your torso using your shoulder, elbow and wrist joints to help position your hand to complete a task. The latter situation is better than the former.

If you have spasticity and find it hard to reach away from your torso, you may tend to ‘throw’ your more-affected arm at a task mainly by activating your shoulder joint. This stands in contrast to a more controlled movement sequence, where your arm can move away from your torso using your shoulder, elbow and wrist joints to help position your hand to complete a task. The latter situation is better than the former.

Success at reaching therefore needs to be trained for. Building up strength and working for incremental spasticity decline can be worked on at the same time. So, trunk constraint whilst performing task-practice has strong evidence for improving outcomes, because it makes ‘cheating’ nearly impossible to do.

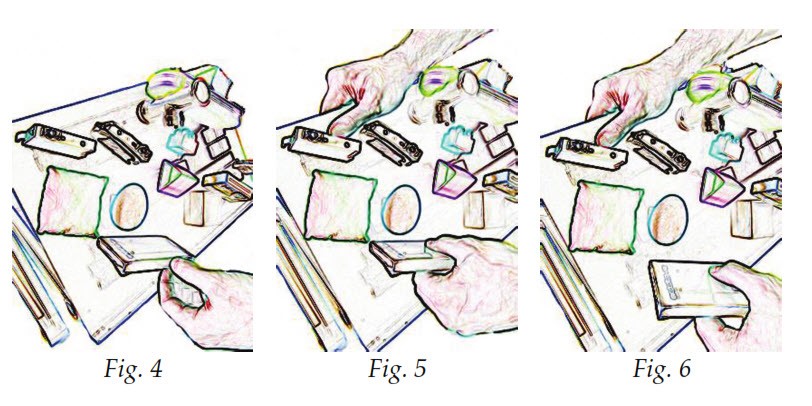

Also, limb de-weighting via wrist holding or using de-weighting technology is a therefore a good way of facilitating this from the start. See picture, below and left. This is because ‘heavy arm’ can render tasks very difficult to perform.

Also, limb de-weighting via wrist holding or using de-weighting technology is a therefore a good way of facilitating this from the start. See picture, below and left. This is because ‘heavy arm’ can render tasks very difficult to perform.

I’ll show you all this in one of the videos, and how a therapist, trainer or any family member can do this precisely to help the survivor ‘get the ‘gap’ between thumb, first finger and middle finger, in order to pick up an object.

So, arm de-weighting, often in terms of assisting in reaching for an item during a task can be used to initiate and/or extend your time practising a task.

One thing you need to know is that although there is evidence that functional control of your hand will only improve once you gain more control over joints which are closer in towards the body (proximal) rather than further away (distal), recent evidence suggests that you should be also be trying to work with your fingers and thumb right from the start rather than waiting for your arm to get stronger in order to position your hand accurately.

This might sound strange if you can’t even ‘get a gap’ between your first finger and your thumb, or that your fingers and thumb are ‘floppy’. Both states would seem to make ‘useful’ hand function non-existent.

This might sound strange if you can’t even ‘get a gap’ between your first finger and your thumb, or that your fingers and thumb are ‘floppy’. Both states would seem to make ‘useful’ hand function non-existent.

However, it’s suggested that, via specific retraining, distal control can and should be trained for immediately after stroke, This is also because if you waited for control to return from proximal to distal, you might achieve some strength in the shoulder, elbow and wrist over time but may not have done any task-specific grasp and release attempts at all, let alone put in the very large amount of intensive retraining time that might stand a chance of helping you regain control of the main reason why you have an arm in the first place.

One Comment

My wife is a stroke survivor of 2 yrs standing. Actually 2 yrs not standing. She has consistently focussed on her determination to walk again. I have recently bought Tom Balkins book and feel 2 yrs has been lost for Ann.