Many years of research suggests that the mobility and functional dependence of stroke survivors worsen over time and that accessing later rehabilitation becomes increasingly difficult for stroke survivors. This raises the big question: when should your ‘supported care pathway’ end? The ideal answer is ‘when I am better’.

The problem is that stroke survivors rarely simply ‘get better’ or ‘get back to normal’. Clinical rehabilitation therefore always has to be a compromise, due to time and resources allocated to professionals and patients. Just ask any hard-working physio or OT! And there are also some specific factors (Approach-specific factors, for example) involved in this compromise which will probably never be fully explained to your satisfaction, even if you were to ask.

Stroke survivors simply tend to know when therapy seems to have ended too soon. They can feel very neglected. Let’s quickly examine Professor Glen Gillen’s handbook ‘Stroke Rehabilitation: A Function-Based Approach’ (a must-get’ read).

Stroke survivors simply tend to know when therapy seems to have ended too soon. They can feel very neglected. Let’s quickly examine Professor Glen Gillen’s handbook ‘Stroke Rehabilitation: A Function-Based Approach’ (a must-get’ read).

In it is an inspirational account from his colleague, the late Professor Barbara Neuhaus (Director of Columbia University’s Programs in Occupational Therapy) who had a stroke in later life and wrote an inspirational description of her resilience and fighting back against her new limitations.

When she got back home from the hospital, different therapists came to her house and assessed her. All three independently signed off that she was too advanced to receive home therapy and so she lost eligibility for further therapy because she was too ‘well’.

Yet instead of feeling elated that these three professionals had all independently agreed she was well, she just felt abandoned and let-down and certainly felt that her rehab was very far indeed from complete.

I’m not sure this squares with US clinical practice guidelines concerning management of adult stroke rehabilitation care:

‘Patients who have sustained an acute stroke should receive rehabilitation services if their post-stroke functional status is below their pre-stroke status, and if there is a potential for improvement. If pre-and post-stroke functional status is equivalent, or if the prognosis is judged to be poor, rehabilitation services may not be appropriate for the patient at the present time’.

Is it that this community therapy failed to recognise the requirement for further rehabilitation, was there no money or time to help her further or was what they felt they could do for her in itself limited at the time? I don’t know. Interesting to speculate though.

Back here in the the UK, we know that many people, after discharge from community physio are clearly not ‘well-enough’ not to need further assistance. They may still be stuck in wheelchairs and/or using sticks and orthotics without much of an idea of how to proceed (ie, self-manage, self-rehab, diminish the use of functional aids over time etc) when the care pathway (from the hospital and community teams) has finished.

But really, it has to be said that the NHS has 99 times out of 100 (or so!) done their very best for them, with usually outstanding pathway – from critical life-saving care all the way to other leading-edge follow-up services such as Prof Nick Ward’s Upper Limb Clinic, which I hope will be used as a blueprint for similar services in hospitals around the UK.

But here’s the thing. Community therapy obviously should phase into a much, much longer, joined-up and structured period of support. And I think all involved in stroke care would agree with me. But it can’t. The questions to be asked are then: who can help, and who will pay for it. Big questions.

A partial answer to the first may possibly be to activate a rung of professional therapists and exercise trainers to support the hospitals in the way that ARNI has done for years. The answer to the second is unclear and outside the remit of this blog!

Back to ‘what happens after therapy’. There is an interesting review of a workshop carried out by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) that I accessed way back in in 2009 that examines services for people who have had a stroke and their carers. The conclusions from the workshop echo the same stories we are told at ARNI every day. Some of the people involved were even our past patients and carers.

The report includes the comment which I get nearly every day on the phone from stroke survivors and carers as a way to precede asking for help. Quoting from the CQC document: “…often people have been given very negative prognoses. They write you off totally, giving you no hope.” It’s important to acknowledge that once YOU BELIEVE that someone who you view as representing the medical profession has told you this, there’s not much you can do to undo having been told it! It’s the way you respond to it that counts.

My view about this for many years is that often people won’t actually have been told ‘you’ll never move this limb again’, or similar, but it’s what they’ve come to understand as the sum result of the ‘it’s not ethical not give my patient false hope’ thing.

It’s actually the only way possible to proceed clinically, but the net result is people either simply giving up before they start, or go the opposite direction and going at their rehab with renewed vigour ‘to spite’ the consultant/physio or whoever they have labelled as the naysayer! I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard this with stroke survivors who train with me. Personally, I’m not sure it’s helpful to give little hope to people – I hear this less and less now, thank goodness.

Back to a few more of the issues raised in this 2009 workshop. The people involved discussed how the physiotherapy they had received had been very good and said the physiotherapists had really cared for them. One participant mentioned how the physiotherapists had helped him get out of the house which was really important to his recovery (turning point) and commented that he still keeps in touch with them. The group discussed, however, that therapists are under a lot of pressure and some commented that their physiotherapy service had been cut-off after a certain period of time.

One stroke survivor felt that whilst in his experience the physiotherapy was very good in hospital, the physiotherapists never explained the purpose of the exercises they were given and how they would help. Another participant highlighted the importance of physiotherapists explaining the reason and importance of carrying out exercises. Some people talked about finding further help merely ‘by chance’, and said that they needed help navigating ‘the system’.

Another stroke survivor described how when he had a stroke he was declared medically unfit for work, ‘thrown out’; and had nowhere to turn. He went to the Citizens Advice Bureau but they did not have the expertise. On the medical side, he was simply sent home with no support or back up. He was told he would make a full recovery and had his benefits taken away. He said it was not until two years after his stroke that he was referred to the Stroke Association for informational help. Another stated that independent services are bewildering and it is very difficult to see what you might be able to get to fulfil your needs and help you live. He expressed the view that the voluntary sector is often better than state care services in this regard.

A carer said that the intensive physiotherapy received in hospital was not followed up after discharge, and that they had to wait several weeks after going home for home-based physiotherapy to start. She added that physio (once a week for 6 weeks) was not adequate and that, although instruction sheets were given for practising between sessions, there was no ongoing support after that time. As a result she paid for private therapy.

But then maybe services in general have improved across the board in the 10 years since this CQC Report.

So, what do you think? Does community therapy end too quickly? And what can community services do better to support physical rehab? Also, what does usual clinical care tend not to concentrate on enough for individuals before discharge?

Like so many people, I didn’t really know much about strokes. I didn’t understand what they were and what effects they have. I thought it was something that only affects the old and unhealthy. I was very very wrong. Strokes can happen to anybody, any age, any fitness, any race. It does not distinguish between how much money you have, how good of a person you are or what your religion is. When it strikes, it strikes without warning, without prejudice and without mercy.

Like so many people, I didn’t really know much about strokes. I didn’t understand what they were and what effects they have. I thought it was something that only affects the old and unhealthy. I was very very wrong. Strokes can happen to anybody, any age, any fitness, any race. It does not distinguish between how much money you have, how good of a person you are or what your religion is. When it strikes, it strikes without warning, without prejudice and without mercy.

Early discharges from hospitals are a good idea to free up hospital beds and to get you back to familiar surroundings once again. But only if the support mechanism of your further ‘re-training’ is in place. Often the support can finish too quickly, leaving survivors (and usually their families/carers too) worried about what to do next, and who to go to for further help. Outpatient therapy and community care, or the lack of it, is often quite wrongly, blamed for not solving all problems.

Early discharges from hospitals are a good idea to free up hospital beds and to get you back to familiar surroundings once again. But only if the support mechanism of your further ‘re-training’ is in place. Often the support can finish too quickly, leaving survivors (and usually their families/carers too) worried about what to do next, and who to go to for further help. Outpatient therapy and community care, or the lack of it, is often quite wrongly, blamed for not solving all problems. This information will include a summary of your rehabilitation progress and your current goals, your diagnosis and your current health status. Functional abilities, which include communication needs are included as well as your care needs – washing, dressing, going to the toilet, eating and so on.

This information will include a summary of your rehabilitation progress and your current goals, your diagnosis and your current health status. Functional abilities, which include communication needs are included as well as your care needs – washing, dressing, going to the toilet, eating and so on.

Aphasia is more common than you might think.

Aphasia is more common than you might think. The PLORAS research study

The PLORAS research study Updates on the progress of their research can be found on their

Updates on the progress of their research can be found on their

Welcome to the new Data Laws coming in to effect tomorrow: May 25th.

Welcome to the new Data Laws coming in to effect tomorrow: May 25th.

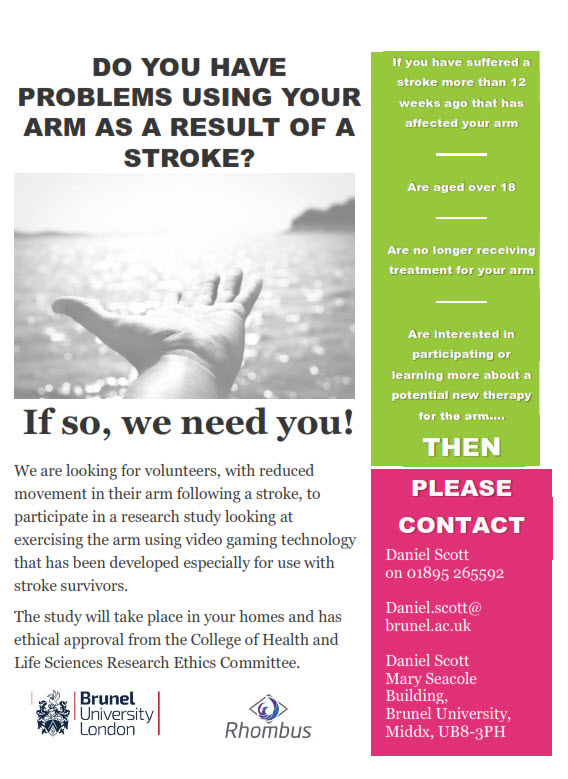

For a participant, the study will begin with a researcher attending the participants in their homes to perform a baseline assessment. One week later the researcher will deliver the Gameball device and train the participant how to use the device. The participant will then be asked to progressively increase the amount of time they use the device over the first week they have it. After that first week the participants will be asked to use the device as much as safely possible for 6 weeks. The participant will have the Gameball for a total of 7 weeks before the researcher then collects the Gameball and performs an assessment. The researcher will return 4 weeks later to perform a final follow up assessment. The total process will last 12 weeks.

For a participant, the study will begin with a researcher attending the participants in their homes to perform a baseline assessment. One week later the researcher will deliver the Gameball device and train the participant how to use the device. The participant will then be asked to progressively increase the amount of time they use the device over the first week they have it. After that first week the participants will be asked to use the device as much as safely possible for 6 weeks. The participant will have the Gameball for a total of 7 weeks before the researcher then collects the Gameball and performs an assessment. The researcher will return 4 weeks later to perform a final follow up assessment. The total process will last 12 weeks.

The aim for this study is to research a treatment method to see if can improve upper limb function.

The aim for this study is to research a treatment method to see if can improve upper limb function.

Professor in Cognitive Neuroscience at UCL, Cathy Price, spoke about how people recover the power of speech after stroke. She confirmed that not being able to speak to family and friends is one of the most devastating consequences of stroke. Patients desperately want to know if they will recover but currently, clinicians can’t provide accurate predictions. Cathy and her PLORAS team are predicting recovery based on which parts of the brain have been damaged by the stroke. The results are proving to be much more useful than previous methods. The goal is to improve the quality of life for as many stroke patients as possible.

Professor in Cognitive Neuroscience at UCL, Cathy Price, spoke about how people recover the power of speech after stroke. She confirmed that not being able to speak to family and friends is one of the most devastating consequences of stroke. Patients desperately want to know if they will recover but currently, clinicians can’t provide accurate predictions. Cathy and her PLORAS team are predicting recovery based on which parts of the brain have been damaged by the stroke. The results are proving to be much more useful than previous methods. The goal is to improve the quality of life for as many stroke patients as possible.

Stroke survivors simply tend to know when therapy seems to have ended too soon. They can feel very neglected. Let’s quickly examine Professor Glen Gillen’s handbook ‘

Stroke survivors simply tend to know when therapy seems to have ended too soon. They can feel very neglected. Let’s quickly examine Professor Glen Gillen’s handbook ‘