As a stroke survivor, you probably heard the term ‘goal setting’ from your multi-disciplinary team who helped you in ‘the early days’. This is because goal setting is considered ‘best practice’ in clinical stroke rehabilitation and its benefits are well recognised. Let’s have a look now about how to translate this practice into something that you can do by yourself when you get home, by yourself or with collaboration from a family member or friend.,

First, it is recognised that even though goal setting is embedded within community-based stroke rehabilitation given by NHS, practice does vary and is potentially sub-optimal. Further, to date, few randomised controlled trials have been completed to demonstrate that goal setting makes a unique contribution to stroke survivors’ rehabilitation outcomes.

First, it is recognised that even though goal setting is embedded within community-based stroke rehabilitation given by NHS, practice does vary and is potentially sub-optimal. Further, to date, few randomised controlled trials have been completed to demonstrate that goal setting makes a unique contribution to stroke survivors’ rehabilitation outcomes.

You have received 6 weeks of community therapy, or you may have had much more, but many people after stroke feel that therapy ended much quicker than you may have liked. And if this therapy is now in the past, you will may possibly feel that it hasn’t optimally prepared you to try and haul yourself through the aftermath of stroke: ie, coping and trying to flourish as a stroke survivor, minimising multiple physical and psychological problems you may have been left with.

Unsurprisingly, a common denominator of many stroke survivors is that they believe (important to stress ‘believe’) that they have not been shown how to rehabilitate themselves effectively going forward.

Most usually understand that they need to ‘retrain’ themselves somehow, and are keen to go for it. And their supporters are keen to help them achieve their goals. But the same people hit a common wall, because they cast about in vain to find the best single way forward. It can take years for stroke survivors to exhaust presented (often very expensive) options, not realising that they had considerable power all that time to change their ‘status quo’, by planning and working out how to deliver self-set goals.

Often, not easy to do – but not particularly difficult either. Where does this leave ‘goals’? Will those things that the multi-disciplinary teams agreed with you to achieve in the community be the same kind of things you need to work out in the ‘real world’ and tackle as you move further away from from your time of stroke?

Often, not easy to do – but not particularly difficult either. Where does this leave ‘goals’? Will those things that the multi-disciplinary teams agreed with you to achieve in the community be the same kind of things you need to work out in the ‘real world’ and tackle as you move further away from from your time of stroke?

And how are goals supposed to be set and stuck to without that ‘negotiationary’ aspect to the process that the therapists helped you with in hospital and during community therapy?

All reasonable questions – let’s break it down to component parts:

Overall, most stroke survivors want to ‘normalise and de-medicalise’ their lives again. They can set goals to do this.

Goals are things you would like to achieve. Many stroke survivors will want to restore lost function, and be able to do the things that they could do before their stroke. These are broad aims that may seem unachievable, and they may not know how to start, but defining goals can help then to break these aims down into smaller, more achievable goals.

Goal setting involves some planning and thought, but usually does not take overly long to do. It basically provides you with the steps to move from where you are now, to where you want to be. You’ll find it to be an empowering process, giving you the chance to take control of your rehabilitation.

To do this, you’re going to ‘get specific’ and ALSO ‘get broad’. Stroke survivors often have very individual hopes for the here and now, and also for the future, in terms of the goals they would like to achieve.

So. once all your therapy finishes, how do you do it? All good questions. To find out the answer, let’s get back to basics.

Where to start.

1 – Identify your goals!

When thinking about goal setting, the first thing to do is identify your goals, ask yourself ‘What do I want to achieve?’

When setting personal goals, specificity is king. For example, just challenging yourself to “do more work” is way too vague, as you’ve got no way of tracking your progress, and no endpoint. Simply put, if your goals aren’t quantifiable, achieving success can be challenging.

When setting personal goals, specificity is king. For example, just challenging yourself to “do more work” is way too vague, as you’ve got no way of tracking your progress, and no endpoint. Simply put, if your goals aren’t quantifiable, achieving success can be challenging.

SMART goals can the answer, as you can break them down into five quantifiable factors.

Try and look at goals in this way: they should be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic/results-based/relevant and timely (SMART). These specific goals should be meaningful to you, and be a mix of highly achievable and reasonable. That said, its good to throw a few unlikely ones in to the mix, which you can do your best at achieving.

Include short-term, mid-term and longer-term goals. Rehabilitation is a journey and takes time. Your goals will reflect this.

By the way, goals that move you forward are almost ALWAYS ABOUT YOU.. DOING THINGS. Not THINGS BEING DONE UNTO YOU.

And in the meantime so much can happen or, in particular, not happen.

Let me stress that you don’t have to become fanatical to achieve success in stroke recovery. Many stroke survivors are living day to day feeling frustrated with their lot. But frustration doesn’t negate intrinsic motivation. This motivation is drive you stimulation/drive you to start, and persevere.

Here some examples of common goals;

Here some examples of common goals;

- To walk indoors independently

- To walk upstairs safely using a hand rail

- To dress upper body independently, threading t shirt over weak arm

- To stand to pull up trousers

- To be able to cut a slice of bread

- To butter toast

- To manage independent exercise programme

To maintain range of movement in hand, wrist and elbow

To maintain range of movement in hand, wrist and elbow- To open a tablet bottle

- To remember when to take my tablets

- To know what my medication is for

- To get in and out of the car safely

- To be able to type an e-mail accurately

- To practice golf on a driving range

EXAMPLE: So, perhaps you would like to walk upstairs independently. Great! That might be a longer-term goal. First you must be able to stand with support. Then, you need to be able to lift one leg and support your weight with the other leg. Then you need to move yourself up a step. Review what you can do now and work from there. Stepping up could be a very difficult thing to do straight away, so your short-term goals might include specific exercises, for example marching, or squats, that strengthen the muscles that you need to climb the stairs. Once you have mastered this, you could increase the repetitions, or move on to stepping up to a low step. Then increase the height of the step, or the number of steps, and so on, until you complete the longer term goal of walking up stairs independently.

Whatever your personal goal, the trick is to break it down into smaller, achievable tasks.

Big Tips from Tom –

- Be ambitious but get someone to help you regulate your ambitiousness: in practice, ‘run it past someone who knows you well”,

- Reveal your limitations: if one of your primary goals is not to reveal your limitations for as many hours of the day as is possible, this can create an anti-risk paradigm towards your recuperation and self-training, it is highly unlikely you will do what it takes to progress.

Prioritise what you want to achieve. Hey, you don’t have to think about working out how to master everything at once… too many goals and trying to accomplish them is far too overwhelming and exhausting. Work out what you want to aim for first, and move to step 2.

2– Make a plan

Once you have identified your goals, you can start planning for their achievement and work out how to incorporate this into your routine.

Once you have identified your goals, you can start planning for their achievement and work out how to incorporate this into your routine.

How will you measure your progress, and over what time-scale? For example, you decide to master a few smaller steps before reaching for the staircase. But, how will you know when to move onto the next challenge? You might get bored with stepping up a few steps, and run the risk of becoming disheartened or become content to just do that, losing sight of your original longer-term goal. Instead, your goal could be to step up 10 small steps after 4 weeks. This is a time-specific and measurable goal. It keeps you focused and gives you something specific to aim for.

When you can measure goals, you can appreciate your progress, and this is so motivating! Thousands of people have found this very thing out after stroke. Just what you need to keep you moving forward.

Involve family, friends and carers. Their input is valuable, and you might want their help. They might think of things that you haven’t thought of, or provide that supportive arm, and it can helpful to get their perspective. They will be part of your journey. Time to start on that journey – move to Step 3.

3 – Do it!

Armed with your planner – do your ‘retraining’, practising formally and also by simply doing activities of daily-life. Record what you’re doing. Don’t overload yourself, but make sure you challenge yourself.

Armed with your planner – do your ‘retraining’, practising formally and also by simply doing activities of daily-life. Record what you’re doing. Don’t overload yourself, but make sure you challenge yourself.

A great tip for you would be: in retraining situations it is important to advance quickly toward practice of whole tasks with as much of the environment context made available as possible. For example, say, a goal of yours is to improve the action control of your paretic foot for being able to cope whilst walking outside, unsupervised and with no supports. The best retraining you can get is to ask a trainer or friend to plan a route for you to go with him or her, so that you can trial it safely and under careful supervision. You can work on leaving a stick behind or reducing the use of an AFO according to your current levels of ability.

A unifying similarity amongst successful stroke survivors is not cognitive or affective (relating to moods, feelings, and attitudes), but willingness to strive for goals deemed ‘unachievable’ for them by those around them (as worked out in your Steps 1 and 2).

CLICK PIC OF STROKE SURVIVOR DOING THE THREE PEAKS CHALLENGE WITH ONE OF OUR ARNI INSTRUCTORS, KIERON FRANKLIN FROM POOLE, WHO HAS TAKEN SOME OF HIS STROKE SURVIVORS ON THIS FOR THE LAST 2 YEARS. DONATE TO ‘MOUNTEMBER 2019‘ IF YOU’RE FEELING GENEROUS!

Tip – motivation is key – if you’re not intrinsically motivated, you’ll have no incentive to push beyond generally accepted boundaries.

4 – Review your goals regularly.

Life may take you in another direction, changing the attainability or suitability of your goals. You may be working towards them faster or slower than you anticipated, or may find that other goals have taken priority. Whatever is happening in your life, it is perfectly OK to adapt or change your goals to suit you where you are now.

Keep talking with the people close to you, try to stay positive and motivated. Also, help/guide others who are going through a similar experience, if you come into contact with them in person or online – this actually has an effect to keep YOU motivated…

5 – Identify barriers to effective goal setting, then adapt and overcome.

Barriers could include communication difficulties, cognitive impairment, fatigue, mood disorders, other health conditions and even a lack of knowledge or understanding of your problems/condition.

If you feel you may have these, or other barriers, don’t let it stop you setting your own goals.

If you feel you may have these, or other barriers, don’t let it stop you setting your own goals.

Take time to ensure that your goals are what you want to achieve. Try to enlist the support of positive people who will take the time to work through what you want to achieve, whether they are family or carers, or therapists/instructors. Positivity breeds positivity.

Be aware of your limitations, but almost everyone can improve and become more functional. Listen to your body and adapt your goals accordingly. You could just break them down to smaller tasks, or do them a different way.

If you are too fatigued, don’t struggle. Rest and return to the task more refreshed.

Educate yourself; there is a wealth of information available about stroke and self-help online and through books.

You can read more about goal setting in The Successful Stroke Survivor, as well as lots of innovative ways to encourage rehabilitation after stroke.

What if I need more help?

Working with a therapist or trainer can be really motivating. This collaboration combines your initiative and drive with the knowledge and experience of a professional. For example, ARNI instructors are specifically trained in methods of stroke rehabilitation and will work with you to identify goals that are functional and personal to you, and together you will strive to achieve them. Empowering you to take control of your rehabilitation.

CALL ARNI now on 0203 053 0111 or write in to receive an info pack through the post.

A study being completed by Tom Oliani as part of his doctorate in Clinical Psychology at the University of Sheffield concerns well-being after stroke.

A study being completed by Tom Oliani as part of his doctorate in Clinical Psychology at the University of Sheffield concerns well-being after stroke.

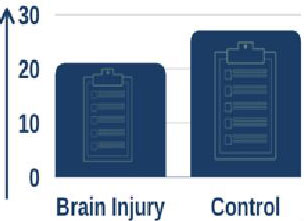

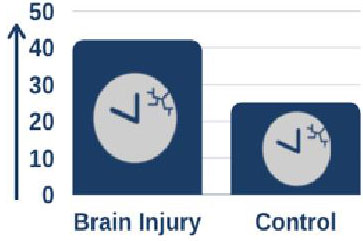

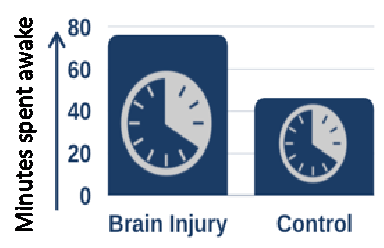

Furthermore, using sleep monitoring wrist watches they showed that, on average, people with brain injury had more disrupted sleep and spent more time awake overnight.

Furthermore, using sleep monitoring wrist watches they showed that, on average, people with brain injury had more disrupted sleep and spent more time awake overnight. When looking at recovery of functional independence over the time spent in the rehabilitation unit, people with brain injury who had more consistent, less disrupted sleep recovered more quickly than those who had more disrupted sleep.

When looking at recovery of functional independence over the time spent in the rehabilitation unit, people with brain injury who had more consistent, less disrupted sleep recovered more quickly than those who had more disrupted sleep. Dr Fleming reports: “As we anticipated, people in hospital following brain injury generally don’t sleep as well as people who haven’t had a brain injury and are at home. What is really interesting is that people who sleep better seem to recovery more quickly and have better outcomes from their rehabilitation.”

Dr Fleming reports: “As we anticipated, people in hospital following brain injury generally don’t sleep as well as people who haven’t had a brain injury and are at home. What is really interesting is that people who sleep better seem to recovery more quickly and have better outcomes from their rehabilitation.”

With a revealing Foreword by broadcaster Andrew Marr, himself a stroke survivor, this seriously practical book reveals everything you need to know about for real-life, evidence-based recovery from limitations caused by stroke, that you can actually understand, use and apply successfully for yourself.

With a revealing Foreword by broadcaster Andrew Marr, himself a stroke survivor, this seriously practical book reveals everything you need to know about for real-life, evidence-based recovery from limitations caused by stroke, that you can actually understand, use and apply successfully for yourself.

Every stroke results in different outcomes, dependent on thousands of variables. A clear-cut background to stroke and the problems it may cause is presented. The author is a stroke survivor who has created and refined over the last 20 years, via his Charity, The ARNI Institute, the innovative ARNI approach to stroke rehabilitation. Here he shows you exactly:

Every stroke results in different outcomes, dependent on thousands of variables. A clear-cut background to stroke and the problems it may cause is presented. The author is a stroke survivor who has created and refined over the last 20 years, via his Charity, The ARNI Institute, the innovative ARNI approach to stroke rehabilitation. Here he shows you exactly:

Endorsed with the Stroke Specific Framework Quality Mark (Reg. No 19755) by the United Kingdom Forum for Stroke Training and Education (UKSF).

Endorsed with the Stroke Specific Framework Quality Mark (Reg. No 19755) by the United Kingdom Forum for Stroke Training and Education (UKSF). Review 1: ‘Who better to write a guide to stroke recovery than someone who has had one? And of those, there can be none better than Tom. He is smart, and studied the science to find ways to go beyond the usual. No quackery, this, but an inspirational and practical evidence and experienced-based recipe for recovery. I strongly commend it’. Review by

Review 1: ‘Who better to write a guide to stroke recovery than someone who has had one? And of those, there can be none better than Tom. He is smart, and studied the science to find ways to go beyond the usual. No quackery, this, but an inspirational and practical evidence and experienced-based recipe for recovery. I strongly commend it’. Review by  Review 2: ‘This comprehensive and empowering book is a must-read for stroke survivors and their families. The book uses Tom Balchin’s own experience of stroke, his knowledge of stroke as well as his work with others over the past two decades. It is highly readable and provides clear explanations of every step of the stroke journey as well as no-nonsense practical steps that everyone can take to improve their quality of life after stroke’. Review by

Review 2: ‘This comprehensive and empowering book is a must-read for stroke survivors and their families. The book uses Tom Balchin’s own experience of stroke, his knowledge of stroke as well as his work with others over the past two decades. It is highly readable and provides clear explanations of every step of the stroke journey as well as no-nonsense practical steps that everyone can take to improve their quality of life after stroke’. Review by  Review 3: ‘Combining his academic expertise and clinical learning, Dr Balchin delivers an exceptional high quality text book for a wide target audience. In this wonderful guide, patients and families will find the essential knowledge they need to help maximise recovery potential after a stroke (or for that matter any injury of the nervous system). He also shows the rehabilitation professional the critical importance of empowering the patient to master their own rehabilitation’. Review by

Review 3: ‘Combining his academic expertise and clinical learning, Dr Balchin delivers an exceptional high quality text book for a wide target audience. In this wonderful guide, patients and families will find the essential knowledge they need to help maximise recovery potential after a stroke (or for that matter any injury of the nervous system). He also shows the rehabilitation professional the critical importance of empowering the patient to master their own rehabilitation’. Review by  Review 4: ‘This is an engaging, easy to read book, suitable for anyone on their journey following a stroke as well as for their family, friends and carers. It focuses on how to personally tailor the retraining of mind and body to optimise recovery from stroke. The messages contained here from Tom instil hope and confidence, and a desire to try yet harder and achieve great things that matter to the individual; yet the book is also written with compassion and kindness to accept limitations that may remain. Thank you, Tom, for putting together this road-map to recovery for stroke survivors’. Review by

Review 4: ‘This is an engaging, easy to read book, suitable for anyone on their journey following a stroke as well as for their family, friends and carers. It focuses on how to personally tailor the retraining of mind and body to optimise recovery from stroke. The messages contained here from Tom instil hope and confidence, and a desire to try yet harder and achieve great things that matter to the individual; yet the book is also written with compassion and kindness to accept limitations that may remain. Thank you, Tom, for putting together this road-map to recovery for stroke survivors’. Review by

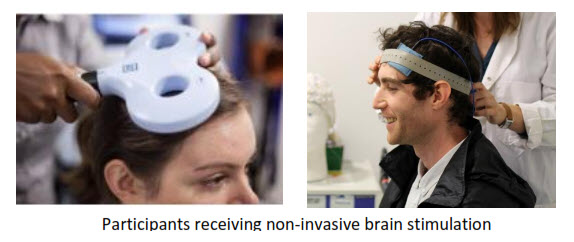

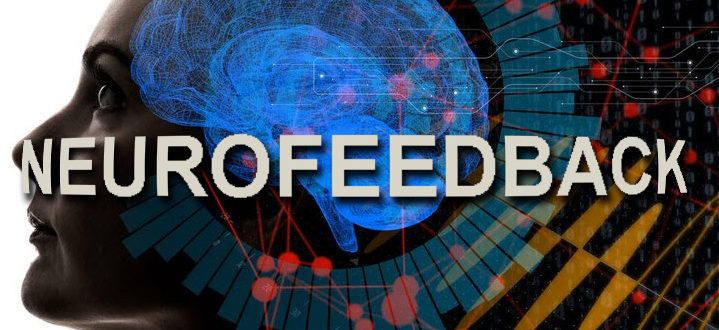

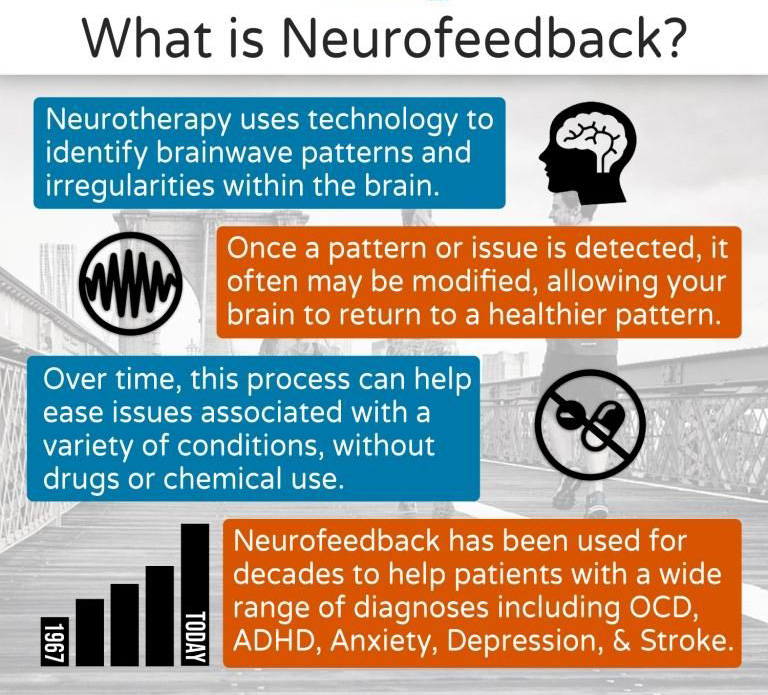

Neuromodulatory non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques are experimental therapies for improving motor function after stroke. The aim of neuromodulation is to enhance adaptive or suppress maladaptive processes of post-stroke reorganisation. However, results on the effectiveness of these methods, which include transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) are

Neuromodulatory non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques are experimental therapies for improving motor function after stroke. The aim of neuromodulation is to enhance adaptive or suppress maladaptive processes of post-stroke reorganisation. However, results on the effectiveness of these methods, which include transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) are

During sessions, you will watch a nature documentary while having very weak brain stimulation. Brain stimulation feels like a warm, tingling sensation on your head.

During sessions, you will watch a nature documentary while having very weak brain stimulation. Brain stimulation feels like a warm, tingling sensation on your head. Ms. Jenny Lee

Ms. Jenny Lee

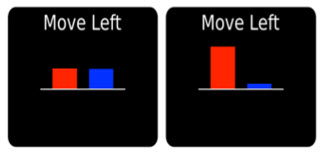

Neurofeedback is a brain scanning (MRI) technique that shows an individual a representation of their own brain activity while doing a task, so they can observe their brain activity and try to adapt it.

Neurofeedback is a brain scanning (MRI) technique that shows an individual a representation of their own brain activity while doing a task, so they can observe their brain activity and try to adapt it. Feedback of brain activity as seen by the participants.

Feedback of brain activity as seen by the participants. Upon interviewing those who have taken part already, participants’ responses have been overwhelmingly positive, specifying both the enjoyment and fulfilment involved with taking part as well as a benefit to their motor recovery.

Upon interviewing those who have taken part already, participants’ responses have been overwhelmingly positive, specifying both the enjoyment and fulfilment involved with taking part as well as a benefit to their motor recovery.

There is converging evidence that more therapy might result in better outcomes: current evidence suggests that intensive rehabilitation therapy helps people regain movement in their affected arm in the first few months after stroke. However, stroke survivors get to believe that little (if any) improvement can be made later on, which is sad, because we know this is not true.

There is converging evidence that more therapy might result in better outcomes: current evidence suggests that intensive rehabilitation therapy helps people regain movement in their affected arm in the first few months after stroke. However, stroke survivors get to believe that little (if any) improvement can be made later on, which is sad, because we know this is not true.

He also needs to recruit a control group of stroke survivors who have been left with some degree of arm weakness but who are not going through the QSUL programme… and who would like to come into the motor control lab at Queen Square for two testing sessions with him. These would be approximately 3 weeks apart and you would be performing the same robotic arm reaching tasks and simple clinical tests of arm movement and strength as the patients who have gone through the full programme.

He also needs to recruit a control group of stroke survivors who have been left with some degree of arm weakness but who are not going through the QSUL programme… and who would like to come into the motor control lab at Queen Square for two testing sessions with him. These would be approximately 3 weeks apart and you would be performing the same robotic arm reaching tasks and simple clinical tests of arm movement and strength as the patients who have gone through the full programme.

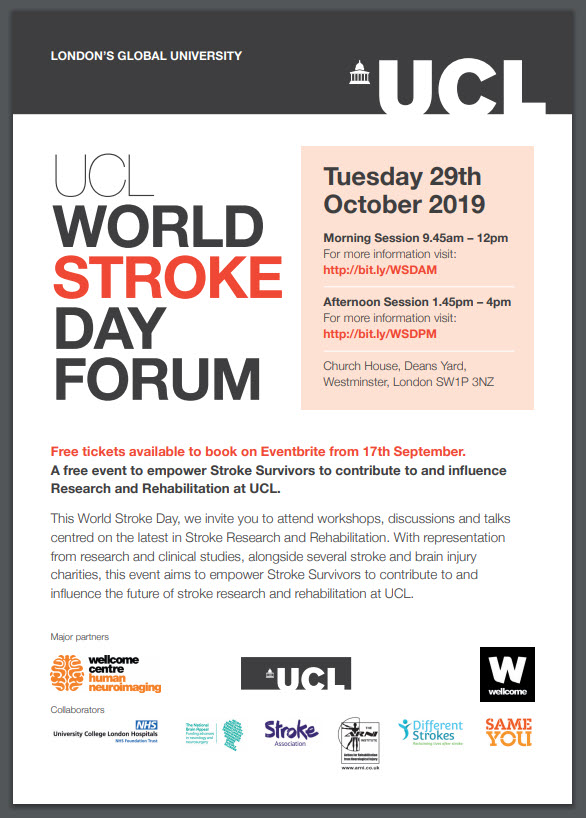

Switched-on stroke survivors are aware that the neurorehabilitation evidence base updates continually. But are you keeping current enough to help yourself optimally? Find out at the UCL World Stroke Day Forum!

Switched-on stroke survivors are aware that the neurorehabilitation evidence base updates continually. But are you keeping current enough to help yourself optimally? Find out at the UCL World Stroke Day Forum! The event will host a number of open talks and workshops, covering topics as diverse as speech rehabilitation, functional rehabilitation, post-stroke fatigue and life as a younger stroke survivor.

The event will host a number of open talks and workshops, covering topics as diverse as speech rehabilitation, functional rehabilitation, post-stroke fatigue and life as a younger stroke survivor. Timings and Sessions for Morning Session (Afternoon Session similar)

Timings and Sessions for Morning Session (Afternoon Session similar) All attendees will be provided with a UCL World Stroke Day Forum bag and a program of available talks and workshops on the day. The event is open primarily to Stroke Survivors and their friends and families, but there are also spots available for practitioners. Please specify the type of free ticket you require on ordering. Tickets are free and distribution will end at 4pm on 28th October 2019. If you would prefer to book tickets for the afternoon event instead, follow this link:

All attendees will be provided with a UCL World Stroke Day Forum bag and a program of available talks and workshops on the day. The event is open primarily to Stroke Survivors and their friends and families, but there are also spots available for practitioners. Please specify the type of free ticket you require on ordering. Tickets are free and distribution will end at 4pm on 28th October 2019. If you would prefer to book tickets for the afternoon event instead, follow this link:

First, it is recognised that even though goal setting is embedded within community-based stroke rehabilitation given by NHS, practice does vary and is potentially sub-optimal. Further, to date, few randomised controlled trials have been completed to demonstrate that goal setting makes a unique contribution to stroke survivors’ rehabilitation outcomes.

First, it is recognised that even though goal setting is embedded within community-based stroke rehabilitation given by NHS, practice does vary and is potentially sub-optimal. Further, to date, few randomised controlled trials have been completed to demonstrate that goal setting makes a unique contribution to stroke survivors’ rehabilitation outcomes. Often, not easy to do – but not particularly difficult either. Where does this leave ‘goals’? Will those things that the multi-disciplinary teams agreed with you to achieve in the community be the same kind of things you need to work out in the ‘real world’ and tackle as you move further away from from your time of stroke?

Often, not easy to do – but not particularly difficult either. Where does this leave ‘goals’? Will those things that the multi-disciplinary teams agreed with you to achieve in the community be the same kind of things you need to work out in the ‘real world’ and tackle as you move further away from from your time of stroke? When setting personal goals, specificity is king. For example, just challenging yourself to “do more work” is way too vague, as you’ve got no way of tracking your progress, and no endpoint. Simply put, if your goals aren’t quantifiable, achieving success can be challenging.

When setting personal goals, specificity is king. For example, just challenging yourself to “do more work” is way too vague, as you’ve got no way of tracking your progress, and no endpoint. Simply put, if your goals aren’t quantifiable, achieving success can be challenging. Here some examples of common goals;

Here some examples of common goals; To maintain range of movement in hand, wrist and elbow

To maintain range of movement in hand, wrist and elbow

Once you have identified your goals, you can start planning for their achievement and work out how to incorporate this into your routine.

Once you have identified your goals, you can start planning for their achievement and work out how to incorporate this into your routine.

If you feel you may have these, or other barriers, don’t let it stop you setting your own goals.

If you feel you may have these, or other barriers, don’t let it stop you setting your own goals.