Lots of people know that recording what they do in retraining helps them to improve their retraining after stroke.

Lots of people know that recording what they do in retraining helps them to improve their retraining after stroke.

You can do the ‘Basics Is Best’ approach: concentrate on doing during your self-retraining time, what you can do, with reference to a customised plan. And then record it. And then refer to your recording when you need to.

BUT THIS ALL VARIES ACORDING TO WHO YOU ARE.

Do you need a planner? Yes and no. Many people prefer to go freestyle (loose-plan), and since I had a stroke in 1997, I’ve done just that. This is because you can ‘group around’ just 4 or 5 of the most essential exercises to do and progress at them.

Do you need to record training? Yes. And I’ll explain why, below.

Do you need to evaluate your training records? Yes and no. I’ll explain more below, don’t worry!

I hope the above doesn’t make you run a mile! Because as with all things, retraining can be much more complex than this if you wanted it to be. But believe me, it doesn’t have to be. It can be ultra-simple.

Let me prove it to you. But bear in mind that my ‘big own secret’ to my success has always been the recording of training.

I’ve returned from total paresis on one side of my body to near full function. But I still need to retrain, 24 years on, in a way that mirrors those wanting to get stronger and fitter. The big key that has emerged from the research, as far as I’ve concerned, is that increasing one’s performance in both aspects plays a direct part in increasing functional control. Plus smart use of the adjuncts (the myriad of interventions available to you).

First, confusion must not be allowed into your retraining. A (loose) plan is needed

A simple way to view improvement is to think about the word ‘progression‘ as it applies to you. Progress is fulfilling and exciting…and it personalises your training. It creates interest in your own improvement. So how can you measure progress? I put it to you that measuring progress yourself is hard! Even neurophysios ‘measuring’ your status and improvement can be wrong, although they can certainly help you to narrow down a picture for you of your own presentation at a point in time.

A few of the people who I’ve trained become upset because they don’t feel they are getting much more progress, even though they feel they are working as ‘smartly’ as possible, and think it’s because they’re doing something wrong. When one analyses their self-training, it’s almost always because they have missed out being guided onto training on the basics, given no progressive training plan that stands a chance of working for them and they also don’t actually record progress even though it is always strongly advised by neurophysios.

At ARNI, for instance, when these people are reminded how they really were physically and mentally a few months before, they can see that actually, progress is still coming in steadily and well. Often, once the ‘big fixes’ have worked, there is a period where progress cannot visibly be seen week to week, and may often appear to be going backwards. It is at these points that the steady recording of training details pays dividends to put progression in perspective.

At ARNI, for instance, when these people are reminded how they really were physically and mentally a few months before, they can see that actually, progress is still coming in steadily and well. Often, once the ‘big fixes’ have worked, there is a period where progress cannot visibly be seen week to week, and may often appear to be going backwards. It is at these points that the steady recording of training details pays dividends to put progression in perspective.

Remember, your recovering brain may play tricks on you. Even after, say 6 sessions of working with ARNI, you have moved from nearly being able to shuffle along with two helpers holding you up, to being able to get off the floor unaided and walking independently without a stick for twenty yards, you may still think you’ve not made progress. You might laugh, but I’ve seen it happen too many times for it to be amusing anymore.

It’s fair to say that even though I have told so many people about how well training diaries which accompany retraining work, only a few people have ever shown me that they use them.

The people who do have all excelled in their retraining and progressively got back new movement evidenced by ability to do new tasks and activities. This is why I really want you to record your progress.

Recording of ‘work done’ is something that can be done really easily. ‘Many a mickle makes a muckle’, and all that. All you need to do is make notes in a box or just tick pre-made boxes. And days go by into months, into years, very quickly.

You’ll create your very own ‘record of success’. Why wouldn’t you do it, really?

Some people can get away without using a training diary, but it is not a good idea. It creates interest and a bond to training. It means that training is not just an abstract thing you do a couple of times a week: it means that you are ‘tied’ to it.

If the stroke has not affected your writing, reading or vision, buy (or ask a friend or relative to buy for you) a diary. or use an Excel spreadsheet or something similar if you are computer literate. It’s the cheapest and best thing you can do for your own rehab.

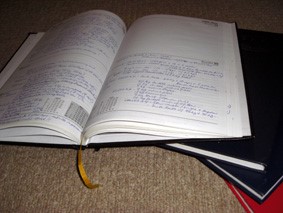

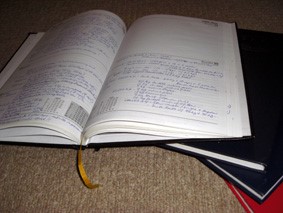

If you get a diary, make sure it’s A4 size. Through experience I’ve found that the A6 or A5 diaries don’t give me the feedback I need. Buy one with a week spread out over 2 pages. Basically, you want to be able to see your whole week.

Get the leather bound variety: why not? You’re worth it. Get one with gold-blocking on the front. Why not? This needs to be something visible and ‘of worth’, not something that can get lost. A coffee-table thing. You are not only going to record the exercises you did in this diary, but you will record briefly how you felt and other details which I’ll note further down in this info-blog.

Get the leather bound variety: why not? You’re worth it. Get one with gold-blocking on the front. Why not? This needs to be something visible and ‘of worth’, not something that can get lost. A coffee-table thing. You are not only going to record the exercises you did in this diary, but you will record briefly how you felt and other details which I’ll note further down in this info-blog.

In the end YOU need to make sure that YOU invest the time in YOU. And, this time should be recorded. Otherwise you can simply go into a ‘holding pattern’ of neither doing badly, but not doing particularly well either.

Remember the ‘toy duck in a bath syndrome’ analogy from by book/manual: The Successful Stroke Survivor?

At its most simple (and it should be simple), a glance to last week’s note should be all that’s required to set a planner of ‘what to shoot for’ this time. In terms of the other aspect (what are you finding it easier to do?), this can also be a place to record that information and information on progression can be gleaned from tiny but progressive gains made in a tiny core group exercises (no more than 4, trained weekly), with 3 minor ones trained daily, plus fitness work. This does of course require you to be cognitively ok also, in order to this. Further external measures are also vital indicators but often not fully necessary (or consistently necessary).

My ARNI trainers all keep records of their sessions with survivors (we send this to the survivor and instructor to work with together). This has been ARNI protocol for at least the last 10 years, and it works well.

My ARNI trainers all keep records of their sessions with survivors (we send this to the survivor and instructor to work with together). This has been ARNI protocol for at least the last 10 years, and it works well.

Instructors set ‘homework’: one to five key movements, that if worked upon, might open up scope for new function. And there is usually a very clear correlation between those who indicate that they are not doing any rehabilitation work outside of class, and non-progress.

We have even had some stroke survivors who, in class are extremely dedicated. But when they turn up each week and are questioned and their training records (of whatever sort) noted, it’s clear they have done nothing. In the end, you don’t ask. And in the end, they sometimes leave because their progress is not as it should/could be.

I’ve also found that the oldest stroke survivors usually accept that a high level of inability to perform activities will be with them through the rest of their lives, and do not believe that it is worth the effort and time trying to change things a little. I do understand this belief and it’s ok. But I wish to offer my own belief that whoever you are, whatever your age, you should do your best to help yourself consistently. If not for yourself and for your own life-state from now on, then for those who love you and care for you.

You can’t rely on your best friend, your partner or your parent telling you that you ‘seem to be doing much better.’ This isn’t good enough, and it’s hardly objective enough. These loved ones may not tell you the truth or they may not know it. Progression is notoriously hard to ‘measure’. So, you don’t need to. All you do is record what you do. You need to start to record your training then gently create your own feedback (whatever you like)… not just by recording what you manage to do, but how you feel about it too. This feedback should be encouraging but critical: reflecting the truth as far as you can see it. You’re not a neurologist or neurophysio (or unlikely to be), and it doesn’t matter at all.

All you’re doing is recording what you’re doing, and recording how you feel about it. Plus additions like weight, supplementation, sleep patterns, medication – if you want to/need to.

I did, and again it was a big key to my recovery. Did any physio show me how to do this stuff? Absolutely not. I needed to do it because I WANTED my recovery to be excellent. And I took my cues from what I could find out at the time, particularly in hand-exercise books (piano-exercises) and formative weight training books.

So, why record?? The reason is that the value is largely in the process of recording, itself. Hardly anyone gets this.

Writing, if one can do it (or typing, I’m sure), also may well contribute to ‘hardwiring’ what one has written or typed into the brain in comparison to just doing something and trying to remember what one has done into the brain.

Furthermore, to be filling in your diary week on week means that you are planning your week around your retraining, even loosely. And you will find that it is a source of enormous self-pride.

The other big key to recording, which I’ve noted no-where else in my texts for survivors, is advice to:

The other big key to recording, which I’ve noted no-where else in my texts for survivors, is advice to:

- Have a plan from the last time you recorded

- Make rough notes on a Post-it, or jotter.

- Take that Post-it into training and annotate it by noting sets and reps with marks and/or numbers and scribbles.

- Then ‘transfer this info into best’ by writing it up in your proper A4 diary.

In this way, you have clear, legible detail that you can add to as you write it all down. Your diary will constantly reinforce the fact that, even if things are ‘going wrong in your progress’, that you are actively doing something about your own physical condition. Week on week, year on year.

At points along the way, you will begin to see patterns of development (or things you can work on) based on the data tracked in your diary. This is useful information for assessing goals. Compared to the amount of hours you will spend with progressively more movement in your lifetime, the few minutes a day (or every couple of days) it takes to make your diary entry is a tiny investment that will reap huge dividends.

Some people never give up their training diaries, and consequently have an amazing record of their rehabilitation. A memoir of lessons learned and goals achieved. What begins as a simple tool to improve training turns into a personal history, an archive, of your life as a stroke survivor rehabilitating.

I personally started to record my own training roughly a year after I had my stroke, and although they morphed into mainly records of my weight training progression (probably a natural requirement for very many other survivors too), it is incredible to look back on now and see what has been achieved. I still have all seven, in a pile. I only stopped because I was doing such freeform training, that I felt that I was at a stage where training (and experimental training) was so much part of my life and routine anyway that recording was unnecessary.

The best advice for stroke survivors reading this, is that at whatever point you are, to start recording your retraining, it will immediately add a sense of purpose, a seriousness and dedication to incremental development. You can easily that a training diary is one of the keys to real body transformation, and it’s so easy to do. I challenge you to do the same.

I buy a training diary for myself and my training partner every year – to just list a few key lifts (the big four) and this has again led directly to solid progression all over again. It’s great.

I buy a training diary for myself and my training partner every year – to just list a few key lifts (the big four) and this has again led directly to solid progression all over again. It’s great.

I’ve also got a much smaller notebook next to my bed where I chock in the date and number of sets and reps of lying on bed hamstring curls and pull-ups. Performance on both of these, for me at any rate, can diminish quickly. So I need to keep track – and not stop.

Some stuff like treadmill 45 degrees fast-walking/weighted-walking doesn’t need to be done, but a marker per day such as half a mile or a mile is a good one. My treadmill is in my office, so it’s hardly a hardship.

Depending on how much you want to use your training diary, besides recording training sessions, you may also decide to use it to record the times when you felt happy because you recognised that progress had been made as you did a specific thing. If you recall something like this, when filling in your training diary, record it too. The more information you gather the better job you (and your therapist or trainer if you have one) can do at managing your training. I remember that for years, we gave stroke survivors who came to see us a ‘Critical Incident Book’. This was not to record how many times they fell over!

We asked them to record any incidences when they found themselves doing something new. The result was a surge of confidence because when they were actively looking for the beginnings of new movements, typically they found themselves doing something unconsciously that they could not do before. One of my clients found that she was reaching for a fridge handle with her paretic hand and trying to open it, so I made sure that she tried to do it again like this each time she encountered her fridge. This became a ‘no-brainer’ ADL task for her, and she trained her brain to do it better and better over time.

In the same way, another lady recorded that she had just walked over a small bridge at her workplace without having to hold on. Even though she moves slowly due to her foot falling to the outside, it is a source of pride to her that she does not hold on, and never allows herself to do it again. Conquering this also means she has also become much better at not clutching onto walls when walking in big rooms. Many stroke survivors will go all the way round the whole wall of a room, however big it is, to avoid walking across it.

Such incidences are exciting because they show that the training is ‘working’, Certainly function is unlikely to be as efficient as before. But switched-on stroke survivors will then use these indicators of movement and work on them as triggers for their everyday rehabilitation.

Such incidences are exciting because they show that the training is ‘working’, Certainly function is unlikely to be as efficient as before. But switched-on stroke survivors will then use these indicators of movement and work on them as triggers for their everyday rehabilitation.

So, doing it (safely) is important. Recording it is equally as important. You are training for you. You must be 100% honest when entering data. Record the quality of your repetitions: the form you use for each exercise must be as consistent as possible every time you train. If you did five good repetitions of a technique, but the sixth needed a tad of help from a family member or trainer, don’t just go ahead and record all six as if they were done under your own steam.

Sounds strict? Yes… but it can become a habit very quickly, and you’ll be very glad you did so. Record the ones you did alone, but note the assisted repetition as only a half repetition.

The order in which you note your exercises is also important for comparison purposes, and this is especially important for strength sessions. If one week the ‘getting up from the floor technique’ is your first exercise and the following week you train this movement at the end of the session, for obvious reasons, you cannot fairly compare your performance over those two sessions. You must, please, be forgiving to yourself regarding your own performance. Training progress is most definitely not linear!

This point goes way back to previous blogs of mine about the nature of success in stroke rehab and also to the points made about creativity in retraining.

Your mission now is to take as much control over your life as you can. Learn from your mistakes. Capitalise on the good things you have done. Do more of the positive things you are already doing and fewer of the negative things. It’s not a daunting task. Just set up a spreadsheet on the computer or use an A4 diary if you can. There are also A5 dedicated training diaries available from ARNI Charity site (shown below), but really, it’s much better to get your own A4 one.

It can make you obsessive about self-rehabilitation. But I’ve not met very many people of the thousands of survivors I’ve met who really are. In fact, there’s no need to be this way.

It can make you obsessive about self-rehabilitation. But I’ve not met very many people of the thousands of survivors I’ve met who really are. In fact, there’s no need to be this way.

Short, progressive 45 minute max sessions daily or once every two days, with additional high dosage daily upper limb work and moderate daily fitness work as required, works much better.

Remember, the more information you gather over time, the better job you (and your physiotherapist or trainer if you have one) can do at managing your training. So the better records you keep, the better you are going to get. This is exactly the zone in which you need to be operating in as a successful stroke survivor, where each mini-success build on mini success. Iterative success. And you’ll see these successes translating into more functionality in daily life.

Many factors like fatigue or pain may mean that you simply won’t be able to do so much rehabilitation for yourself at first – but these require observation, evaluation and management. You will soon understand that retraining can help you with each of these two – and so it will merge with your lifestyle… and that lifestyle is certainly not all about retraining. It just becomes something you ‘do’, alongside everything else in your life. And that’s the free key to stroke rehab success I offer to you today!

And as a reward for reading this far (!), do feel free to email me personally on tom@arni.uk.com to ask for my whole 7 DVD set for just £30 including postage and packing. This is down from the original £100 including postage and packing.

See video below (which has sound switched off: it’s not your pc!).

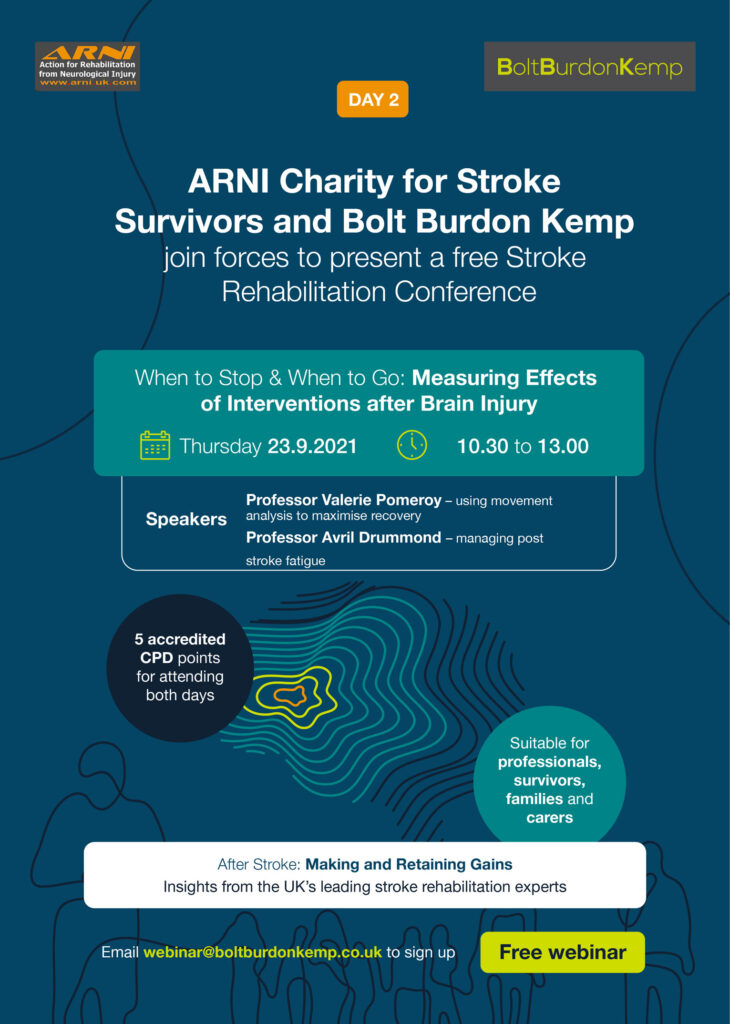

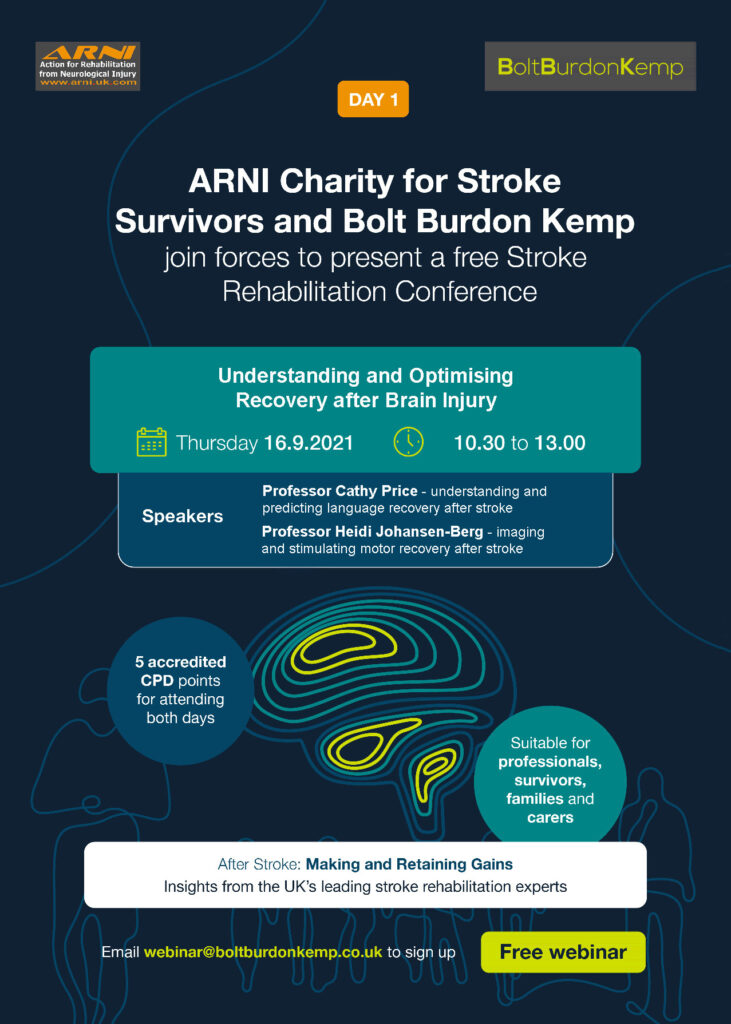

On 16th and 23rd September, ARNI and BBK are holding two COMPLETELY FREE 2.5 hour stroke rehabilitation event/discussions for survivors and their families, and for professionals who help those with brain injury.

On 16th and 23rd September, ARNI and BBK are holding two COMPLETELY FREE 2.5 hour stroke rehabilitation event/discussions for survivors and their families, and for professionals who help those with brain injury.

With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent mandatory lockdowns that followed, performing rehab exercises prescribed by physiotherapists, at home without help (save some telerehab options) was and still continues to be the most usual mode of rehab available for some stroke survivors.

With the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent mandatory lockdowns that followed, performing rehab exercises prescribed by physiotherapists, at home without help (save some telerehab options) was and still continues to be the most usual mode of rehab available for some stroke survivors. In simple terms, self-efficacy can be described as the beliefs an individual has towards their ability to successfully perform a task or achieve a certain outcome, in this case completing home exercise.

In simple terms, self-efficacy can be described as the beliefs an individual has towards their ability to successfully perform a task or achieve a certain outcome, in this case completing home exercise.

Lots of people know that recording what they do in retraining helps them to improve their retraining after stroke.

Lots of people know that recording what they do in retraining helps them to improve their retraining after stroke. Get the leather bound variety: why not? You’re worth it. Get one with gold-blocking on the front. Why not? This needs to be something visible and ‘of worth’, not something that can get lost. A coffee-table thing. You are not only going to record the exercises you did in this diary, but you will record briefly how you felt and other details which I’ll note further down in this info-blog.

Get the leather bound variety: why not? You’re worth it. Get one with gold-blocking on the front. Why not? This needs to be something visible and ‘of worth’, not something that can get lost. A coffee-table thing. You are not only going to record the exercises you did in this diary, but you will record briefly how you felt and other details which I’ll note further down in this info-blog. My ARNI trainers all keep records of their sessions with survivors (we send this to the survivor and instructor to work with together). This has been ARNI protocol for at least the last 10 years, and it works well.

My ARNI trainers all keep records of their sessions with survivors (we send this to the survivor and instructor to work with together). This has been ARNI protocol for at least the last 10 years, and it works well. The other big key to recording, which I’ve noted no-where else in my texts for survivors, is advice to:

The other big key to recording, which I’ve noted no-where else in my texts for survivors, is advice to: I buy a training diary for myself and my training partner every year – to just list a few key lifts (the big four) and this has again led directly to solid progression all over again. It’s great.

I buy a training diary for myself and my training partner every year – to just list a few key lifts (the big four) and this has again led directly to solid progression all over again. It’s great. It can make you obsessive about self-rehabilitation. But I’ve not met very many people of the thousands of survivors I’ve met who really are. In fact, there’s no need to be this way.

It can make you obsessive about self-rehabilitation. But I’ve not met very many people of the thousands of survivors I’ve met who really are. In fact, there’s no need to be this way.

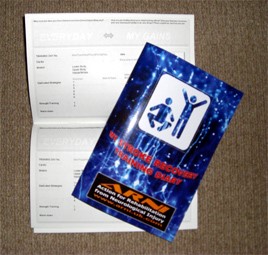

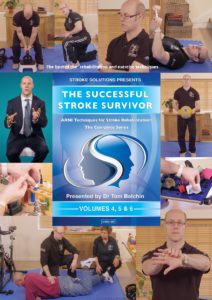

He will show you how to recover balance, how to walk and turn without problem, how to cope with drop foot, how to reach, grasp and release well again, how to become stronger and robust.. and how to tackle all sorts of activities of daily life that you hadn’t dreamed possible after stroke.

He will show you how to recover balance, how to walk and turn without problem, how to cope with drop foot, how to reach, grasp and release well again, how to become stronger and robust.. and how to tackle all sorts of activities of daily life that you hadn’t dreamed possible after stroke. You can do it: Dr Tom will show you how, and in the Bonus DVD, will also show you a full training session with a stroke survivor so you can see how everything works.

You can do it: Dr Tom will show you how, and in the Bonus DVD, will also show you a full training session with a stroke survivor so you can see how everything works.

Research has suggested a lack of physical activity as a significant risk factor for stroke, suggesting increasing exercise and physical activity levels may aid stroke prevention by providing significant health benefits. Strong evidence exists to support this, suggesting aerobic exercise improves an individual’s heart health and vascular profile, through reducing total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, reducing blood pressure and enhancing glucose regulation. These health improvements can prevent many stroke-inducing conditions, including obesity and type-2 diabetes, suggesting the positive role of exercise in preventing recurring stroke.

Research has suggested a lack of physical activity as a significant risk factor for stroke, suggesting increasing exercise and physical activity levels may aid stroke prevention by providing significant health benefits. Strong evidence exists to support this, suggesting aerobic exercise improves an individual’s heart health and vascular profile, through reducing total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, reducing blood pressure and enhancing glucose regulation. These health improvements can prevent many stroke-inducing conditions, including obesity and type-2 diabetes, suggesting the positive role of exercise in preventing recurring stroke. Aerobic physical activity can also provide psychological benefits. Mental health benefits have been observed in a number of research studies, with concomitant reduction of depression rates being noted.

Aerobic physical activity can also provide psychological benefits. Mental health benefits have been observed in a number of research studies, with concomitant reduction of depression rates being noted.

Nottingham University hopes this research will help them to add to the evidence of how we can improve UK cardiac rehabilitation opportunities amongst stroke survivors…

Nottingham University hopes this research will help them to add to the evidence of how we can improve UK cardiac rehabilitation opportunities amongst stroke survivors…

Strong evidence exists that physiotherapy improves the ability of people to move and be independent after suffering a stroke. But at six months after stroke, we know that many people remain unable to produce the movement needed for every-day activities such as answering a telephone. So, what can be done?

Strong evidence exists that physiotherapy improves the ability of people to move and be independent after suffering a stroke. But at six months after stroke, we know that many people remain unable to produce the movement needed for every-day activities such as answering a telephone. So, what can be done? 2. Second, to optimise a physiotherapist’s chances to advise/work on an optimal combination of rehab interventions for each individual after stroke, it would be ideal to find out what kinds of sleep patterns are most beneficial for them.

2. Second, to optimise a physiotherapist’s chances to advise/work on an optimal combination of rehab interventions for each individual after stroke, it would be ideal to find out what kinds of sleep patterns are most beneficial for them. Ideally, more portable equipment should also be able to be accessed by therapists, which would cost less and is designed for use in small spaces. But such equipment would have to also be sensitive enough to provide meaningful feedback for therapists in a similar way to those used by the specialist labs. Such feedback could then be very useful for therapists and survivors to create optimal rehab plans together which would really enable the survivor to work on his/her edges of current ability.

Ideally, more portable equipment should also be able to be accessed by therapists, which would cost less and is designed for use in small spaces. But such equipment would have to also be sensitive enough to provide meaningful feedback for therapists in a similar way to those used by the specialist labs. Such feedback could then be very useful for therapists and survivors to create optimal rehab plans together which would really enable the survivor to work on his/her edges of current ability. A School of Health Sciences research team at the University of East Anglia (UEA) headed up by

A School of Health Sciences research team at the University of East Anglia (UEA) headed up by

Go for it if you can/if it’s appropriate for you!

Go for it if you can/if it’s appropriate for you!

They’ll then place reflective markers on your skin. These markers are tracked by infra-red cameras placed at the top of the walls of the MoveExLab.

They’ll then place reflective markers on your skin. These markers are tracked by infra-red cameras placed at the top of the walls of the MoveExLab.

A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research concerning venue-based exercise interventions for people with stroke in the UK has just been published in the journal ‘Physiotherapy’. The available evidence base analysed found that the ARNI fares better than Exercise Referral Schemes in terms of survivors making important improvements in activities of daily life (ADL). including eating, dressing and household tasks. ARNI has been found to improve physical function and mobility and importantly, is non-ambulant people inclusive.

A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative research concerning venue-based exercise interventions for people with stroke in the UK has just been published in the journal ‘Physiotherapy’. The available evidence base analysed found that the ARNI fares better than Exercise Referral Schemes in terms of survivors making important improvements in activities of daily life (ADL). including eating, dressing and household tasks. ARNI has been found to improve physical function and mobility and importantly, is non-ambulant people inclusive. But it may be less well-known that engagement with exercise amongst the UK stroke population does not meet published recommendations and that exercise referral participants advised to go to gyms report feeling intimidated in the traditional gym environment. Moreover, that long-term adherence to exercise referral programmes is less than 50%. This is not good at all.

But it may be less well-known that engagement with exercise amongst the UK stroke population does not meet published recommendations and that exercise referral participants advised to go to gyms report feeling intimidated in the traditional gym environment. Moreover, that long-term adherence to exercise referral programmes is less than 50%. This is not good at all. Participants on ARNI programmes feel challenged to push the boundaries of their recovery and experiment with new activities.

Participants on ARNI programmes feel challenged to push the boundaries of their recovery and experiment with new activities. This does make the requirement for the stroke survivor to ‘take back control’ and become as autonomous as possible in his or her ADLs, as key to progression and ‘beating/managing’ the effects of stroke.

This does make the requirement for the stroke survivor to ‘take back control’ and become as autonomous as possible in his or her ADLs, as key to progression and ‘beating/managing’ the effects of stroke.

Thomas Eldred (Verified Purchase) – (USA)

Elvira Oravecz Péter (Verified Purchase) – (Hungary)

Petr Pokorny (Verified Purchase) –

All DVDs are very important to us for my husband, every move is very precious every minute, thanks for the help, we work every day, we learn. We want good health and good luck Enikő and Ernő

Tim Webster (Verified Purchase) –

Full of practical tips, drills and ideas, “THE SUCCESSFUL STROKE SURVIVOR” videos are an excellent resource for stroke survivors.

Suzie (Verified Purchase) –

I definitely recommend these dvds, beautifully presented and easy to follow and very inspirational. I use them now in addition to my private physio to help in my recovery, only wish they were available earlier. Lots of training strategies and exercises developed by Tom, a true expert and stroke survivor. Don’t hesitate buy the complete set.

I am an ARNI instructor in training and I am finding these videos essential in helping me become a knowledgeable, effective and inspired trainer. I purchased the complete set, along with Dr Balchin’s Stroke Survivor book and I refer to them on a daily basis and I know they will continue to be an indispensable tool in my development. Each technique is clearly explained and demonstrated by Tom and the great thing is that you can pause at any point to try it yourself, or listen back to something. If you are a carer, friend or family member, wanting to help a loved one who has had a stroke then these DVDs are a must.

As a former Royal Marine, these exercises have been paramount in improving the functional use of both my arm and hand. I would wholly recommend ‘DVD Volume 5’ to anyone who wishes to improve their condition, following a stroke.

Russ Kennedy (Verified Purchase) – (USA)

It’s my pleasure to recommend the Stroke Solutions DVD. I purchased the book, The Successful Stroke Survivor, about five years ago but found that I needed to be shown how to do certain exercises. Since I have obtained the affordable and worthwhile DVD, I continually refer to it. I wish that you had been able to make it available sooner. Many thanks. Russ Kennedy PhD, MBA, MPH

Justin Smallwood (Verified Purchase) –(UK)

Peter Corfield (Verified Purchase) –(France)

I had an AVM stroke 1st June 2010.We were in France. My wife found me on the floor having returned from an art experience there was no way of telling how long I had been there. Maybe 4/5 hours or longer a helicopter was called from Dijon I was flown to a hospital in a coma. Missed out on the view. They did an emergency craniotomy to repair the vein that had burst .I was put in an induced coma for about 2 and a half weeks. When I awoke I was hemiplegic left side. Enough about me. These DVDs are so Amazing I can’t tell you how good they are in words try them yourself. I may even do some of the exercises as my you tube stroke blog when I have enough time in the day . You may have seen me armchair gardening filling and emptying the dishwasher fetching the wood. Everyday life can be achieved after stroke and I owe it all to Dr. Tom Balchin and Arni Institute. Buy the DVDs they are Awesome.

Nick Cole (Verified Purchase) –(UK)

Finally, all his knowledge is distilled into a set of DVDs. They’re pure gold dust, refined over many years experience working with stroke survivors of all ages. I’m working through the exercises in the DVDs and they still form the basis of my twice-weekly physiotherapy and self-rehab programme.

Louis Rowson (Verified Purchase) –(UK)

Found the DVDs very inspirational, I have had a lot of help from the wonderful therapists in North Devon, but need now to move on and I believe Tom’s DVDs will help me. My initial prognosis left me wheelchair bound, but with determination and support I can now walk with support, my left hand is still of very little use but I have been given fresh motivation by the DVDs.

These DVDs are beautifully and compassionately presented by Dr Tom Balchin and his team! Every move, exercise, strategy is clearly described and demonstrated, with many repetitions of the complexities of some of the coping strategies and functional training techniques and drills. I recommend these to every stroke survivor and their families, and carers. As an adjunct to ‘The Successful Stroke Survivor’ the DVDs give strong visual and aural cues to the descriptions in the book. This actually makes the learning of, and thus the effective implementation of the strategies, much more accessible.

Gary Sacheck (Verified Purchase) – (USA)

I am a stroke survivor and agree with the statement that, “knowledge is power” and this video plus all those that accompany this in Tom’s collection deliver that specific knowledge that a stroke survivor needs. This video like all in the collection inspire and provide the variety and “make it fun & interesting” style in your exercises to help you keep your rehab progressing.

Owen Thomas (Verified Purchase) –(UK)

Very informative and helpful: clear and concise instructions with great attention to detail on technique! Thank you!