A review paper has just been published in Nature Digital Medicine about UI/UX design requirements for young stroke survivors. UI (User Interface) is the visual, tangible aspect of a product that a user interacts with on a mobile phone or pc, including elements like buttons, icons, and colors, while UX (User Experience) is the overall, internal feeling a user has during their entire interaction with a product or service.

The systematic literature review synthesizes findings from 25 studies to offer recommendations for developing ICT-based rehabilitation and self-management tools for younger stroke survivors (<55 years) and their carers. It found that participatory co-design with stroke survivors is essential to ensure interventions meet their specific needs and abilities and that digital tools must be further adapted for post-stroke impairments like:

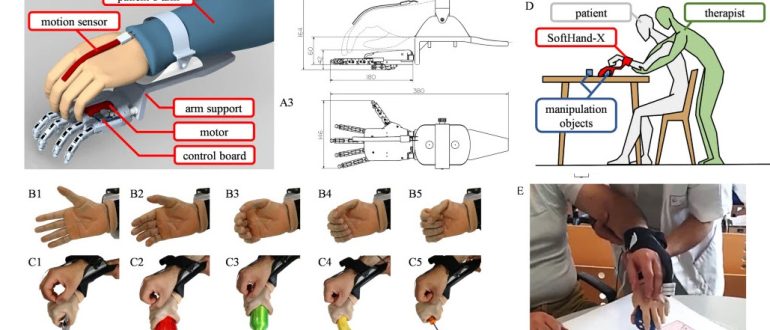

- Hemiparesis: which can make controlling a mouse or using a standard keyboard difficult. The interface must support one-sided use for those with hemiparesis and use larger, clearly clickable buttons.

- Cognitive changes: cognitive fatigue, memory issues, and difficulty with complex tasks can hinder prolonged engagement. For survivors with aphasia, the recommended readability level is grade 5 or lower, a standard rarely met by existing tools. This means using simpler language and supplementing text with images and videos.

- Communication challenges: aphasia can make text-heavy interfaces inaccessible and frustrating. Designs should offer multiple modalities to accommodate sensory impairments. This includes using larger graphics and clear, non-distracting sound effects.

- Sensory impairments: reduced vision or hearing require multimodal design approaches. Designs should minimize overwhelming sensory and activity overload. This can be achieved by limiting options per screen, using simple, tranquil interfaces without complex background images or flashing elements and avoiding loud or distracting background music.